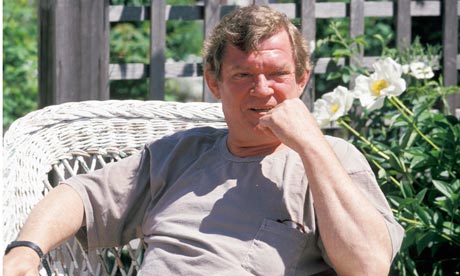

Robert Hughes: the greatest art critic of our time

Rude, hilarious, eloquent, but never petty ... the Australian writer, who has died aged 74, made criticism look like literature

Robert Hughes, who has died aged 74, was simply the greatest art critic of our time and it will be a long while before we see his like again. He made criticism look like literature. He also made it look morally worthwhile. He lent a nobility to what can often seem a petty way to spend your life. Hughes could be savage, but he was never petty. There was purpose to his lightning bolts of condemnation.

That larger sense of purpose can best be seen in his two classic books on art, The Shock of the New and Nothing If Not Critical. The first is the book of his great BBC television series about the story of modern art. For Hughes, it is a tragic story. He believed he lived after the end of the great creative age of modernism. I remember, watching the television series as a teenager, how excitingly he described the Paris in the 1900s, when motor cars and the Eiffel Tower were young and Picasso was painting Les Demoiselles d'Avignon. But Hughes would not tolerate any glib pretensions that art in 1980 (when The Shock of the New aired) lived up to that original starburst of modern energy. For him, Andy Warhol was an emotionally thin artist bleached by celebrity, and Joseph Beuys ... Well, he didn't have much time for Beuys.

It was as if the BBC had commissioned the 18th-century satirist Jonathan Swift to make a documentary about modern life.

Hughes makes his anger with the depths that art has sunk to even clearer in the essays gathered in Nothing If Not Critical. For the best part of his career as a critic, he lived in New York. It was the decline he perceived there, from Robert Rauschenberg to Robert Mapplethorpe, that so disgusted him with the fall of modern art. This was a political and ethical judgment, as well as artistic. Art had become the plaything of the market, he believed. It was getting too expensive as it turned into the sport of 1980s investors. Artists like Jeff Koons and – he later added – Damien Hirst were barely real artists at all, but grotesque market manipulators.

If he was right, God help us all, for the conquest of art by money and the proliferation of celebrity artists that he condemned continues to multiply. The art world of today might be mistaken for an apocalyptic vision dredged from his darkest satirical imaginings.

The joy of reading Hughes is infectious and often hilarious. His sheer rudeness can be liberating. His piece on the death of the graffiti painter Jean-Michel Basquiat is brutally titled "Requiem for a Featherweight". Other essays in Nothing If Not Critical call a named art dealer a "sleazeball" and take on the artist Julian Schnabel in a rhetorical standoff involving bullwhips, motorbikes, and, of course, Hughes's utterly damming judgment of Schnabel's work.

Hughes would doubtless see it as one more instance of the art world's absurdity that, while Schnabel was fawned on by curators when the fiery critic was mocking his vacuity, nowadays art fashion sees Schnabel as a silly old expressionist dauber. Schnabel has, however, built a second career in films.

In his final book Rome, this critic whose prose is so majestic and rolling writes about some of his literary heroes. They include the ancient Roman poets Virgil and Juvenal. These Latin authors were the models for the so-called "Augustan" writers of 18th-century Britain in whose style Hughes himself wrote. His power of scorn consciously evokes such works as Swift's Modest Proposal – he even once penned a poem about the art world modelled on Alexander Pope's Dunciad. How many writers of the late 20th century compare with Pope and Swift? Even if you do not agree with a word Hughes wrote or said, the eloquence of his voice makes him a modern classic. At his best, he was a finer writer and sharper polemicist than his friend Christopher Hitchens, a mightier wordsmith than most of today's leading novelists.

Hughes believed in modern art, whose story he told more eloquently than anyone else ever has. He was not some stick-in-the-mud. But he compared art in the 1900s with the art of today and observed that even our best do not deserve comparison with the pioneers of modernism. This is a truth that is hard to refute. The words of Robert Hughes have cost me a lot of sleep.

No comments:

Post a Comment