Today's digital manipulations have created a knowledge crisis. AI can make our eyes and ears see and hear things that seem believable but never took place. Lars Strannegård calls for a strong and subtle knowledge reform.

Lying was long considered something unheard of. A discovered lie was a legitimate reason to terminate a relationship or demand the resignation of a power holder. But lately, a shift has taken place, and it's not just Donald Trump's fault.

The American presidential candidate has certainly made the large-scale lying an art form of his own, apparently inspired by a kind of Soviet shamelessness where the lie's lack of ambition to hide that it is precisely a lie reinforces its character as a means of power: not even trying to pretend to be telling the truth is a particularly icy form of rulership technique.

Among the Klintbergs that have come from the American side lately, the one about Haitian immigrants in Ohio who eat their neighbors' pets may be said to be among the more colorful. That type of public lies is now an ever-present part of our mediatized everyday life; less shameful and easier to get away with than just a few years ago.

The shift in reality we are witnessing today takes place on a different level than before. It is so profound, so existentially challenging that, as Christer Mattson at the Segerstedt Institute has emphasized , we can speak of an ontological crisis. Nowadays, the distortion of reality and the truth is not only about someone claiming something that is not true, and which can be seen by those who know something about the matter.

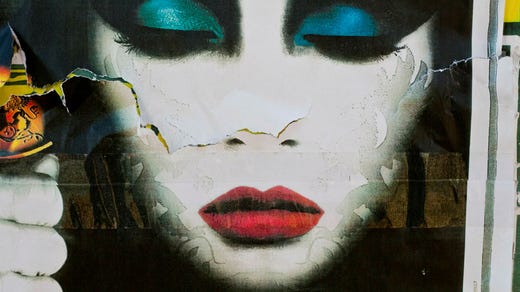

What has happened is that through the artificial intelligence we can be manipulated into seeing and hearing with our own eyes and ears things that appear credible but in fact never took place. The examples of images and videos we thought were authentic, but which turned out to be fabrications, are constantly growing and, with the help of algorithms, get the greatest possible impact in social media. For the vast majority of people, it is almost impossible to validate the veracity of visual and auditory impressions. We neither can nor should believe our own ears anymore.

Ontology is the study of being, that which exists. This is one of the most fundamental areas of philosophy: how the world is made up, and what properties make up its essence. In the abundance of conflicting reality and truth claims created by digital technology, the uncertainty about what actually exists or has actually occurred increases. Our ontologically based judgment is clouded. We don't know if the images we are flooded with are real or generated by AI.

More than forty years ago, Jean Baudrillard wrote that signs of reality were about to replace reality itself, or at least relegate it to the background. The true and real, he feared, was becoming secondary and uninteresting, risking losing value compared to an enhanced, embellished and tightened description of reality. He used the terms "simulation" and "simulacra" to describe an emerging existence where we are unable, or perhaps unwilling, to distinguish between the true reality and the spectacular version of reality. And now we are indeed there.

In a world where images and videos can be total fabrications, the reality that appears before our eyes must be subject to reflection and suspicion, and consequently, more and more media companies stop publishing images from public and unverified sources. Hand in hand with the ontological uncertainty goes its sibling, the epistemological crisis.

Where ontology asks questions about what exists, epistemology - the theory of knowledge - asks how we can know that something exists. What is knowledge? When we can't believe our eyes and ears, we start asking ourselves things like: where does this claim to knowledge come from? How do we know it's true? How is the data generated? And who is it that has an interest in conveying a certain picture of reality?

The almost existential uncertainty that these two crises create has found its way into our inner lives. We can no longer be sure if our attitudes, opinions or feelings are our own. Perhaps they are fabricated by someone else, and so internalized to the point that we believe they are ours. Most frightening is if it happens without us being aware of it, and is led to believe that we have power over ourselves.

Ten years ago, 48 percent of the world's population lived in non-democracies, according to the 2024 democracy report from the University of Gothenburg. The figure has now increased to a breathtaking 78 percent. That a country has had hundreds of years of democratic statehood is therefore no guarantee that it will continue. It is also not a natural law that freedom of expression and academic freedom, however well-established and self-evident they may be, are preserved and flourished by mere automaticity. Nothing is obvious, nothing happens without considered and conscious actions. What we hold dear must be constantly articulated and recreated.

Sweden is usually described as a society of high trust, which is to be regarded as a great asset. In high-trust societies, characterized by inclusion and respect for the basic principles of the rule of law, collaborations occur more friction-free and there is a built-in resistance to sedition. But in times of ontological and epistemological cloudiness, this trust in social institutions and its building blocks, such as meritocracy, the judiciary and democratic elections, weakens.

Manipulations of images, films and truths are highly effective tools for dividing and dividing societies. The feeling that no one and nothing can be trusted results in exhaustion and resignation, which in turn opens the door to increased acceptance of simulacra rather than real truth.

So how should we deal with these two, the ontological and the epistemological crisis? How are we to navigate a media landscape so perforated by false truth claims and simulated realities? As so often, the answer is that individuals' ability to resist and see through manipulations must be trained through practice in fact-finding, reflection, judgment and articulation. Ensuring the facts, critical thinking, interpretation and free expression are more important than ever.

A frighteningly neglected area is image analysis and visual literacy. Despite a culture that is becoming more and more visual, few have actually been trained to understand, decipher and analyze image streams. Here, of course, the education system has a central role. Our schools need to drill young people in image analysis. And our universities need to take their ontological and epistemological responsibility even more seriously. We cannot afford to politicize them and make them tools for anything other than the original mission: to seek truth and knowledge through science and analysis, to critically let reality as it appears before our eyes take place and be interpreted.

The media must have its own credibility at the top of the priority list. They cannot deviate one degree from their press ethical compass. Initiatives aimed at verifying images and videos need to be expanded . Education unions need to conduct training on how best to counter the disintegration of democracy. The manipulated image flow can probably be said to be a greater existential threat than any individual nation, and therefore becomes a matter for Total Defence.

It is high time that we in Sweden create an awareness of how the distortion of our digitized world has profound and existentially challenging consequences for our trust and perception of reality. We fought the pandemic with immunity shots. The crises we are in now can also be combated with vaccinations. But this time in the form of knowledge, awareness and ontological and epistemological sensitivity, instead of needles.

Lars Strannegård

Professor and rector at the Stockholm School of Economics

Listserv moderated by Toyin Falola, University of Texas at Austin

To post to this group, send an email to USAAfricaDialogue@googlegroups.com

To subscribe to this group, send an email to USAAfricaDialogue+subscribe@googlegroups.com

Current archives at http://groups.google.com/group/USAAfricaDialogue

Early archives at http://www.utexas.edu/conferences/africa/ads/index.html

---

You received this message because you are subscribed to the Google Groups "USA Africa Dialogue Series" group.

To unsubscribe from this group and stop receiving emails from it, send an email to usaafricadialogue+unsubscribe@googlegroups.com.

To view this discussion visit https://groups.google.com/d/msgid/usaafricadialogue/7a377e9f-569a-4567-978c-40baa7b20ca2n%40googlegroups.com.

No comments:

Post a Comment