Where, in the name of Jesus Christ, is the Black person, and the African, in particular, going to be fully accepted?

Is it in the place of his ethnic origins, from which many have fled and to which many academics cannot return because it would be like returning to a a condition of existence unthinkable in those very constituencies where they have fled to and where they are descried as facing marginalization?

I have wondered how I could re-integrate myself into the Nigerian environment after an uninterrupted nine to ten years of studying in England. Can I live without constant, uninterrupted electricity? Will solar power be adequate to meet my domestic energy needs? Can I live without constant water delivered by the state, not by my own efforts? Can I live without the confidence of high level safety and comfort in commuting, in which one can travel from London to Cambridge and not encounter a single pot-hole on the road, a journey I have done once by bicycle and mostly at night, a journey that if one were to attempt by car from Lagos to Benin, for example,one would be taking a great risk, as the death toll on that road testifies? Can I do without the ability to have the latest literature in any field delivered to my doorstep within days or weeks of ordering? I dont know how easily Amazon, for example, delivers to Nigeria.

The irony of the whole situation is that my entire existence in England is paid for by my sponsors in Nigeria who are living in those very conditions. If they had not resolved to succeed in business in that demanding country, they could not afford the millions it has taken to enable me take advantage of the comfort of this developed society.

The irony is great.

It would seem, then, that using this report as a point of measurement, that promotion in Nigerian universities, generally speaking, might be more equitable than in British universities. Even though I know little about Nigerian universities, I knew the University of Benin where I worked, had a precise formula for promotion. It was centred on publications. A particular number of publications was/ is required to reach each position. One might be delayed by whatever machinations might emerge in the promotion process,including arbitrary upward reviews of the promotion criteria by professors who themselves have not met and may never meet the new, more demanding criteria, but one would achieve one's goals eventually if one kept working. This report and other anecdotal accounts about promotion in English universities, at least, I have come across suggest the situation might not be so clear cut in Britain.

The British academics are almost certainly much more published than their Nigerian counterparts. In terms of book publications, perhaps comparison can be made by acknowledging the very significant disparities between them since the culture of book publication seems much stronger in England than in Nigeria.. The British post graduate programs are generally likely to be better than those of Nigeria. The British academics, of course, I expect are better paid. They live lives of superior physical comfort. And yet, it seems that the totality of the quality of their lives might not necessarily be higher.

When I did an MA at SOAS at the University of London in 2004, a number of my colleagues and I, both Black and Japanese, concluded that the Black staff of the Faculty of African Languages generally looked harassed and seemed be on emotional tenterhooks. The Caucasian staff, however, looked fully at home. I was shocked to learn that a Black female member of staff in the Faculty of Law was able to win a case against the university for paying her less than her colleagues of the same rank for years. She also alleged consistent putting down by her colleagues who impugned her ability to achieve as an academic. And this a woman who had a PhD from Oxford, the acme of English education.

I wonder how many people share my experience in England, of having so called friends, both Asian and European, who want to be seen with you only in certain clearly defined spaces, or are ready to identify you as a friend only to people not closely acquainted with them, limiting the exposure of your friendship as much as possible, friends, who might not even have achieved up to yourself. The only explanation I have been able to find for that experience is the issue of Blackness. As Peter Enahoro would put it, you gotta cry to laugh.

As much as I considered some of the conditions at the University of Benin primitive when I left there, doubt if anyone could have been underpaid there All staff salaries were public knowledge, all salaries for each grade being circulated in official documentation.

It seems, therefore, that in comparative global education, all is not as it might seem.

I know even less about US education and society, , but I cant forget the Skip Gates saga which I think Obama got right on his first, instinctive response. A policeman handcuffing an elderly man on a walking stick on charges of disturbing the peace because the man was challenging him and perhaps being quarrelsome. I expect that many of us will never forget that experience, though we only experienced it through automatic projection into the person of Gates. Bringing closer the raw urgency of this issue is a knowledge of Gates history, from his father's working at two jobs to pay for his children's education, a father who most likely, did not have a university education himself, to Gates self defining contributions to his field, making him perhaps the most visible Black scholar of his generation, in my view, even as he remains controversial on account of his self positioning within the context of Black and mainstream Caucasian society, a controversy underlined by that drama and its handling by all the parties involved, Gates, the policeman, the Boston police, Harvard, Gates employer, the President, public figures who commented on it, like the then governor of California, Arnold Schwarzenneger, and various people in the US, to appreciate the enormity of the sheer profoundly disturbing can of parasitic social issues that will not go away , without a revolutionary social change.

The question resonates ever more strongly " What's a nigga gotta do to be sure of respect?"

Irele summed up these issues in relation to scholarship in "The African Scholar", published more than 10 years ago. He argued for the relative minimal effect of African scholarship on the global pool of scholarship. He mentioned the assimilation of the Black scholar into scholarly paradigms that his ethnic civilization has made little contribution to. He lamented the prominence of African scholarship on the global stage as evident more in terms of individual reputations than of a reputation emerging from a solid body of collective achievement.

The actual picture might not be so bleak. Rowland Abiodun's paper calling for the use of concepts from classical African aesthetics in the study of African art is likely to have played a role in o the contemporary prominence of that practice in the study of Yoruba art, as I understand it. I wont pretend, though, to be up to dateon any field in African studies talk less of having a synoptic view of African scholarship. Better informed people would be able to help us.

I conclude, though, that regardless of whatever soaring achievements Africans reach abroad, as long as their countries are in such difficult straits they will have problems of respect globally, which is what racism might boil down to. You can publish 5 million books and head NASA. As long as Africa as a whole is not developed or demonstrates very visible consistent progress towards development, I dont expect Africans generally to be highly respected as a group.

The Asians used to be in this situation. Within decades, they have pulled themselves out of it.

Thanks

toyin

On 30 May 2011 14:31, Toyin Falola <toyin.falola@mail.utexas.edu> wrote:

--"14,000 British professors, but only 50 are black appointees in the professorial rank"

Higher Education Statistics Agency reveals number of black professors in UK universities has barely changed in eight years

- by Jessica Shepherd, education correspondent

- Guardian.co.uk, Friday 27 May 2011 19.53 BST

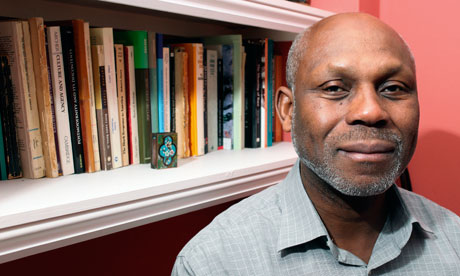

Harry Goulbourne, professor of sociology at London South Bank University, says universities are still riddled with 'passive racism'. Photograph: by Eamonn McCabe for the Guardian

Leading black academics are calling for an urgent culture change at UK universities as figures show there are just 50 black British professors out of more than 14,000, and the number has barely changed in eight years, according to data from the Higher Education Statistics Agency.

Only the University of Birmingham has more than two black British professors, and six out of 133 have more than two black professors from the UK or abroad. The statistics, from 2009/10, define black as Black Caribbean or Black African.

Black academics are demanding urgent action and argue that they have to work twice as hard as their white peers and are passed over for promotion.

A study to be published in October found ethnic minorities at UK universities feel "isolated and marginalised".

Heidi Mirza, an emeritus professor at the Institute of Education, University of London, is demanding new legislation to require universities to tackle discrimination.

Laws brought in last month give employers, including universities, the option to hire someone from an ethnic minority if they are under-represented in their organisation and are as well-qualified for a post as other candidates. This is known as positive action. Mirza wants the law amended so that universities are compelled to use positive action in recruitment.

She said there were too many "soft options" for universities and there needed to be penalties for those that paid lip-service to the under-representation of minorities. Positive discrimination, where an employer can limit recruitment to someone of a particular race or ethnicity, is illegal.

The HESA figures show black British professors make up just 0.4% of all British professors - 50 out of 14,385.

This is despite the fact that 2.8% of the population of England and Wales is Black African or Black Caribbean, according to the Office for National Statistics. Only 10 of the 50 black British professors are women.

The figures reflect professors in post in December 2009. When black professors from overseas were included, the figure rose to 75. This is still 0.4%of all 17,375 professors at UK universities. The six universities with more than two black professors from the UK or overseas include London Metropolitan, Nottingham, and Brunel universities. Some 94.3% of British professors are white, and 3.7% are Asian. Some 1.2% of all academics - not just professors - are black. There are no black vice-chancellorsin the UK.

Harry Goulbourne, professor of sociology at London South Bank University, said that while the crude racism of the past had gone, universities were riddled with "passive racism". He said that, as a black man aspiring to be a professor, he had had to publish twice as many academic papers as his white peers. He said he had switched out of the field of politics, because it was not one that promoted minorities. He called for a "cultural shift" inside the most prestigious universities.

Mirza said UK universities were "nepotistic and cliquey". "It is all about who you know," she said.

Audrey Osler, a visiting professor of education at Leeds University, described the statistics as "a tragedy". "Not just for students, but because they show we are clearly losing some very, very able people from British academia."

Nelarine Cornelius, a professor and associate dean at Bradford University, said that while universities took discrimination very seriously when it came to students, they paid far less attention when it concerned staff.Many of the brightest black students were seeking academic posts in the United States where promotion prospects were fairer, they said. Others said too little was being done to encourage clever black students to consider academia and that many were put off by the relatively low pay and short contracts.

Universities UK - the umbrella group for vice-chancellors - acknowledged that there was a problem. Nicola Dandridge, its chief executive, said: "We recognise that there is a serious issue about lack of black representation among senior staff in universities, though this is not a problem affecting universities alone, but one affecting wider society as a whole."

A study by the Equality Challenge Unit, which promotes equality in higher education, found universities had "informal practices" when it came to promoting staff and that this may be discriminating against ethnic minorities. Its findings, to be published this autumn, will call on universities' equality and diversity departments to be strengthened.

Mirza said she had chaired equality committees at three universities. "We get reports from human resources and say 'oh my goodness, we really need to do something about this'. But the committees are on the margins of the decision-making."

Nicola Rollock, an academic researcher in race and education at the Institute of Education, University of London, said there needed to be greater understanding of how decisions were made inside universities. Equality departments risked being "an appendage" or a monitoring form for people applying for jobs. "We are still far more comfortable talking about social class than race in universities," she said.--Toyin Falola

Department of History

The University of Texas at Austin

1 University Station

Austin, TX 78712-0220

USA

512 475 7224

512 475 7222 (fax)

http://www.toyinfalola.com/

www.utexas.edu/conferences/africa

http://groups.google.com/group/yorubaaffairs

http://groups.google.com/group/USAAfricaDialogue

You received this message because you are subscribed to the "USA-Africa Dialogue Series" moderated by Toyin Falola, University of Texas at Austin.

For current archives, visit http://groups.google.com/group/USAAfricaDialogue

For previous archives, visit http://www.utexas.edu/conferences/africa/ads/index.html

To post to this group, send an email to USAAfricaDialogue@googlegroups.com

To unsubscribe from this group, send an email to USAAfricaDialogue-

unsubscribe@googlegroups.com

You received this message because you are subscribed to the "USA-Africa Dialogue Series" moderated by Toyin Falola, University of Texas at Austin.

For current archives, visit http://groups.google.com/group/USAAfricaDialogue

For previous archives, visit http://www.utexas.edu/conferences/africa/ads/index.html

To post to this group, send an email to USAAfricaDialogue@googlegroups.com

To unsubscribe from this group, send an email to USAAfricaDialogue-

unsubscribe@googlegroups.com

No comments:

Post a Comment